Deleuze on Becoming: An Introduction

I've been tinkering at the edges of

this 'introduction to Deleuze on becoming' for a while, and I finally found some

free time to whack it all together, so - here is a thing I wrote on

Deleuze and becoming. As with all of my posts of Deleuzeian vocabulary, I largely

wrote this for myself, as 'becoming' was and is one of those topics that

I was struggling to 'put together', and this is one of my attempts to

do that for me. Hopefully though, others might find it interesting or

useful! This is not comprehensive - I don't really talk about the

specific becomings that D&G do, like becoming-animal,

becoming-imperceptible on so on, but this is already very long! Any

suggestions, critiques, corrections, or questions are welcome.

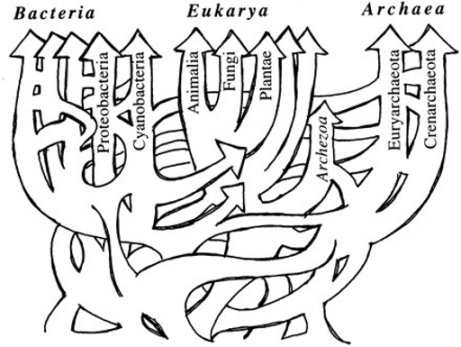

A more accurate, contemporary depiction of the 'tree of life', which shows 'gene transfers' happening at the very bottom of the tree. The relevance of this will be seen later.

§0: Deleuze on Becoming

Deleuze is famously known as a philosopher of 'becoming', but too often the easy acceptance of this glosses over just how strange and original his take on becoming really is. Deleuze doesn't just 'side' with 'becoming' over 'being', but rather creates, almost out of whole cloth, a conception of becoming that challenges almost every cliche about what we usually take becoming to 'be'. What I want to do here is provide something like an introduction to Deleuze's philosophy of becoming, but in particular, I want to trace a singular through-line that persists all throughout his writing on becoming: his attempt to think the consistency of becoming, its independent standing as a concept, as something more than just its usual association with 'flow', 'process', or change. The first thing we'll need to do is clear up the very grammar of becoming.

§1: The Grammar of Becoming

The first thing to set aside is the idea that 'becoming-x' refers to one thing becoming another thing. Becoming is not an intermediate process between two static moments: "There is no terminus from which you set out, none which you arrive at or which you ought to arrive at. Nor are there two terms which are exchanged. The question 'what are you becoming?' is particularly stupid" (Dialogues). Thinking of becoming in that way is to understand it from the point of view of identity, such that becoming is only ever something transitory and ephemeral - between two states of being, as it were. Instead, in the words of Deleuze and Guattari, "becoming is a verb with a consistency all its own" (ATP239).

This reference to becoming as a 'verb' is a clue that Deleuze, in his early work - particularly in the Logic of Sense - pays great attention to. More than just any verb in fact, he refers to becoming as belonging to the order of the 'infinitive' verb: "Verbs in the infinitive are limitless becomings" - infinitives being words like 'to walk' or 'to flee'. What is distinctive about infinitives is that they lack - or, better to say - they have no need for certain properties that other kinds of verbs have. Specifically, they do not require any reference to what are called mood, voice, tense, or person. While these are technical distinctions found among linguists (Deleuze's reference here is most often to the work of the French linguist Gustave Guillaume), the one that will concern Deleuze the most is the lack of any reference to a person - or subject.

Here, in fact, is one of the key reasons why infinitives correlate with becomings: infinitives are 'subjectless', which means they don't refer to a subject which undergoes them, they just subsist on their own: "The verb 'to be' has the characteristic - like an original taint - of referring to an I, at least to a possible one, which overcodes it and puts it in the first person of the indicative. But infinitive-becomings have no subject: they refer only to an 'it' of the event (it is raining) and are themselves attributed to states of things which are compounds or collectives, assemblages, even at the peak of their singularity" (Dialogues). That there is no-thing that undergoes a becoming, that becomings have a subsistence outside and independent of subjects, is given voice to by thinking becoming in terms of the infinitive.

That the infinitive 'sheds' the subject - along with mood, tense, and and voice - is why Deleuze will speak of the infinitive as a 'pure infinitive' - as purified from "the play of grammatical determinations" (LoS214) which other grammatical categories have. The purity of the infinitive corresponds to the purity of becoming, which likewise, is 'disengaged' and 'distinct' from bodies and things: "each time a proud and shiny verb has been disengaged, distinct from things and bodies, states of affairs and their qualities, their actions and passions: like the verb ‘to green’, distinct from the tree and its greenness, or the verb ‘to eat’ (or ‘to be eaten’) distinct from food and its consumable qualities, or the verb ‘to mate’ distinct from bodies and their sexes – eternal truths." (LoS221). Here again, this 'disengagement' speaks again to a certain kind of 'independence' of becoming, which we're looking to thematize here.

[Historical note: one source of this seemingly obscure link between infinitives and becoming is Spinoza. In his book on Spinoza, Expressionism in Philosophy, Deleuze makes reference to Spinoza's Compendium Grammatices Linguae Hebraeae ("Compendium of the Grammar of the Hebrew Language"). There we find the following passage (this translation is from Giorgio Agamben's essay "Absolute Immanence"): "Since it often happens that the agent and patient are one and the same person, the Jews found it necessary to form a new and seventh kind of infinitive with which to express an action referred to both the agent and the patient, an action that thus has the form of both an activity and a passivity ... It was therefore necessary to invent another kind of infinitive, which expressed an action referred to the agent as immanent cause..., which, as we have seen, means 'to visit oneself,' or 'to constitute oneself as visiting', or, finally, 'to show oneself as visiting.'"]

§2: The Temporality of Becoming

In the passage on the 'disengagement' of the infinitive from the Logic of Sense quoted above, at least one other thing ought to stand out immediately for its strangeness: the alignment of the infinitive - and thus becoming - with eternal truths(!). After all, becoming, in its usual sense, is often associated with change. But to think the consistency of becoming is to challenge precisely this alignment. For if becoming has a subsistence independent of any subject that undergoes it, and if subjects are what undergo change, then the mode of temporality proper to becoming is something other than change. To unpack this, it's worth listening to what Deleuze has to say in an interview with Toni Negri, where he makes a very helpful distinction between 'becoming', on the one hand, and 'history', on the other:

"The thing is, I became more and more aware of the possibility of distinguishing between becoming and history ... What history grasps in an event is the way it’s actualized in particular circumstances; the event’s becoming is beyond the scope of history. ... Becoming isn’t part of history; history amounts only the set of preconditions, however recent, that one leaves behind in order to “become,” that is, to create something new". That becoming is 'outside of history' speaks again to the fact that becoming is not just mere change - which operates at the level of history - but that which, as it were, persists across change. This is why, counter-intuitively, becoming in Deleuze has temporal characteristics more closely associated with the unchanging. While in the Logic of Sense becoming is associated with the 'eternal', later, in A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze, with Guattari, refines this a bit by reference to Nietzsche:

"A bit of becoming in the pure state; they are transhistorical. There is no act of creation that is not transhistorical and does not come up from behind or proceed by way of a liberated line. Nietzsche opposes history not to the eternal but to the subhistorical or superhistorical: the Untimely, which is another name for haecceity, becoming, the innocence of becoming (in other words, forgetting as opposed to memory, geography as opposed to history, the map as opposed to the tracing, the rhizome as opposed to arborescence)" (ATP296). These last few characterizations of becoming are useful: becoming as 'forgetting', 'geography', 'map', and 'rhizome'. What is notable is that, with the exception of 'forgetting', the last three terms, 'geography', 'map' and 'rhizome', are largely spatial concepts. In fact, as we'll see, in the progression of Deleuze's thought about becoming, space rather than time, gradually becomes the dominant key in which becoming is considered.

Before we get to space however, we'll take a look at the remaining item on the list: forgetting. In ATP, Deleuze and Guattari could not be more explicit: "becoming is an antimemory". One can read in this: an anti-history. Becoming is an anti-history or an anti-memory insofar as it breaks with the present: "history is made only by those who oppose history". Earlier, in the Logic of Sense, this breaking with the present is explicitly figured in terms of "eluding the present", of "not tolerating the separation or the distinction of before and after, past and future" (LoS1). Here again we should hear the ring of the infinitive verb which, in the register of grammar, similarly does not 'tolerate' the distinctions between 'subject and predicate, active and passive'. In all these cases, what is again attested to is a certain per-sistence of becoming through time, which in turn, similarly attests to it con-sistency, its 'purity' ("becoming in the pure state").

§3: The Heterogeneity of Becoming

So far, it's true that we have largely approached 'becoming' in negative terms: as the 'subjectless' infinitive, or as 'antimemory' and so on. This is partly, I think, because it's not until Deleuze starts to talk of becoming in spatial terms that he truly begins to find the vocabulary most appropriate to it. The spatial terms that Deleuze employs - that of 'territory', 'bloc', belonging 'in the middle', between, and even 'interbeing' - are ways to think about the sense of 'movement' implicit in becoming without resorting to a temporal vocabulary. In other places, Deleuze's poetics are even more dramatic: becoming as 'contagion', 'theft', infection (by vampire), epidemic, or encounter.

What is common to these more 'spatially inflected' senses of movement is that they all imply a certain sense of 'unnaturalness' (a matter of "unnatural participations", ATP241) and discontinuity - as distinct from the continuity of time and history. Better yet, these terms imply a sense of continuity forged from discontinuity, as when D&G talk of "blocs of becoming" which "constitute a zone of proximity and indiscernibility... sweeping up the two distant or contiguous points, carrying one into the proximity of the other" (ATP293). Note here that whether the points are 'distant' or 'contiguous' (side-by-side) is of no consequence - becoming does not respect either distance or proximity, it can take place between utterly heterogeneous elements.

In fact, in perhaps the most celebrated example of 'becoming' in the work of D&G, that of the orchid and the wasp, what is often missed is that the salience of the example comes precisely from the heterogeneity of the coupling: "if evolution includes any veritable becomings, it is in the domain of symbioses that bring into play beings of totally different scales and kingdoms, with no possible filiation. There is a block of becoming that snaps up the wasp and the orchid, but from which no wasp-orchid can ever descend" (ATP238). Once again we can hear in this the way in which becoming is opposed to history, or in this case, genealogy. In some cases, this notion of 'opposition' should be taken literally.

As detailed by the biologist Nick Lane, when what is now called 'endosymbiosis' - the process in which bacteria cooperate with each other so that some cells physically enter into, and become part of others - was first proposed by Lynn Margulis and her colleagues in the 1960s, "their ideas were not forgotten but were laughed out of house as 'too fantastic for present mention in polite biological society" (The Vital Question). Today we know that mitochondria (the powerhouse of the cell!) were incorporated into complex cells precisely in this way (along with many other sub-cell structures). The significance of endosymbiosis is that it is a process of evolutionary change that does not proceed by natural selection. Hence D&G: "transfers of genetic material by viruses or through other procedures, fusions of cells originating in different species ... [are] transversal communications between different lines [that] scramble the genealogical tree... The rhizome is an anti-genealogy" (ATP11).

§4:Conclusion and Illustration

This emphasis on the heterogeneity of becoming - its taking place always 'between two' - furnishes Deleuze with - I think - among his most decisive of philosophical moves: his effort to "overthrow ontology" (ATP25), and substitute a logic of 'AND' for the logic of 'IS'. Here, we come full circle to the grammar of becoming once again: "Thinking with AND, instead of thinking IS, instead of thinking for IS: empiricism has never had another secret" (Dialogues, 57). It is only via the composition of 'AND's (wasp and orchid) that a logic of becoming can be given consistency. This emphasis on the 'AND' has led at least one commentator, François Zourabichvili, to claim, perhaps rightly, that there simply is "no ontology of Deleuze" - such is his commitment to becoming.

To engage in one last clearing maneuver, it's important to note that this logic of 'AND' is not exactly a logic of 'relations' either: "Relations might still establish themselves between their terms, or between two sets, from one to the other, but the AND gives relations another direction, and puts to flight terms and sets, the former and the latter on the line of flight which it actively creates" (Dialogues 57). This is the case insofar as the becoming that takes place between any two elements alters those elements in turn. It is precisely the entire 'bloc' of becoming - the elements and the sustained, ongoing circuit between them, that must be treated as 'a' becoming, or a mutual circuit of becoming, taken entirely on its own terms. To end, I simply want to quote one of my favorite depictions/illustrations of becoming, from the philosopher Alphonso Lingis. These lines will give a little color, I hope, to the largely abstract discussion that's taken place so far:

"A hunter acquires the sharp eyes, the wariness, the stealth movement, the speed, the readiness to spring and race, and the exhilaration of the beast he hunts, which are available for stalking the prey but also gamboling down the hills into the river, dancing, and sexual contests. A forager is bent upon the earth, is herself imbued with the damp and smell of the ground, and acquires the patience of plants. There is symbiosis, for the prey animal contracts the speed and direction of movement of the hunter, and the plants protect themselves with thorns and toxins from, and recover after the passage of the forager... An industrial worker takes on the movements and pacing of the machine, while machines are made to the scale and force of humans.

There are also symbiotic couplings with plants: among the sequoias the woodman’s body does not become ligneous and stiff, but he stands tall, looks skyward, and becomes laconic. There are couplings with the movements of the winds and the rain and of the waves of lakes, with the frozen tundra and the tropical swamps. There are movements that take on the movements of cells and of molecules and scintillations of light. ... At the limit the anorganic organism picking up multiple movements and trajectories of its environment, entering into multidimensional symbiosis with it, loses itself, becomes imperceptible, anorganic, nonsignifying, nonsubjective, impersonal in its environment, and thereby produces a world, one world among innumerable others, connected to them" (Lingis, "Defenestration").

Comments

Post a Comment